test 10/17/22

Bishop of the People: Enrique Angelelli

Mixture of earth and heaven

Design both human and the divine.

Whose face is seen in every human being,

And whose history forms a people.

Enrique Angelelli

From the moment Pope Francis assumed office, the new pontiff has spoken with a remarkable clarity and freshness of vision. In doing so he has drawn deeply from of a religious culture matured in South America and from personalities that profoundly influenced his early priesthood. Among these was an Argentinean bishop by the name of Enrique Angelelli.

As the vast pampas spread and rise east of Buena Aires metropolis, the land gradually becomes more arid, the towns smaller and further apart. Twelve hours by car from the Argentine capital, the prairies give way to the desert province of La Rioja and eventually town of Anilacco, a whitewashed scattering of dwellings, where the bell tower of the small church was still unfinished a hundred years after its construction had begun. As unvarying as the salt grass, the town clung to the desert but never seemed to change — until the day that the new bishop arrived in a Volkswagen pickup truck. Stepping out from behind the wheel, the burley, energetic young man exuded remarkable warmth and an uncommon touch. He met with the people, drank mate (the native tea) with them, and listened. Bishop Angelelli would later say, that he kept “one ear to the Gospel, the other to the common folk.”

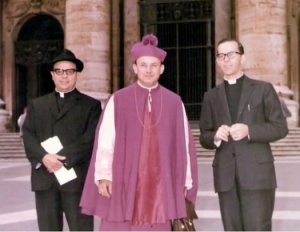

Bishop Enrique Angelelli in Rome particiapting in the Second Vatican Council. At the time he was the youngest bishop ever appoointed to Argentina.

Born the son of an immigrant vegetable farmer in Cordoba, Argentina, he had studied in Rome and began his priestly ministry working with youth groups, and in shantytowns. Appointed as auxiliary bishop in Cordoba in 1960, he took part in the Second Vatican Council and in 1968 was assigned by Pope Paul VI to head the rural diocese of La Rioja. In a sermon given by Bishop Angelelli at his installation Mass he affirmed the importance of viewing “hunger, ignorance, and misery” in the light of the Gospel, and expressed a desire to serve all regardless of class, or ideology.”

The young bishop cast a wide net in a region where the church had long been considered the preserve of the upper classes. To better reach the rural populations, Angelelli initiated a weekly radio Mass from his cathedral, and celebrated Mass in the fields, and reached out to groups that hitherto had had little connection with the Church: poets, painters, labor leaders, and journalists. Angelelli also involved himself in labor issues. Attracting younger priests and nuns to his diocese, the bishop promoted a cooperative of women weavers and a labor union for maids.Inevitably, he came to deal with the issue of Anilacco’s one untapped resource: several hundred acres of vineyard that had sat abandoned for several decades.

Always a man of the people, the bishop appears alongside members of his flock with the stole that he often wore in public.

Had the province of La Rioja been a world unto itself the community of Anilacco might have peacefully resolved its differences. But Argentina in the 1970s was a nation in crisis. Responding to the kidnapping and murder of prominent public figures by a relatively small number of Marxist revolutionaries, the Argentine military aggressively pursued anyone suspected of communist leanings. It was a struggle waged without compromise, and in a country where “to be a loyal Argentinean, was to be a Catholic,” the struggle quickly assumed religious overtones. It was suggested that the Church had lost its way after Vatican II under the leadership of the “Red Pope,” Paul VI. Clergy and lay leaders engaged in social justice issues were frequently labeled Communists, and jailed, tortured, and even executed as threats to the fatherland.

In such circumstances the charismatic bishop found himself in contention with a group of Anilacco landowners. They feared that the reopening of the abandoned vineyards would cause a reduction in the water available to till their own fields. But in the climate of the time, and despite the fact that the bishop enjoyed the support of the provincial governor, the issue ballooned into a religious confrontation.

On a cold, windy Wednesday morning in June 1973, the streets outside the church at Anilacco were crowded with school children and families to greet the Archbishop on the occasion of the parish feast of St. Anthony of Padua. Banners of various religious groups flapped in the wind, and the bishop arriving in his telltale pickup truck, along with several other priests and nuns, was enthusiastically greeted. As they crowded into the tall narrow church, the townspeople looked forward to the procession around the town plaza, followed by games, food, and music.

Shortly after Mass began, a group of 13 prominent winegrowers and businessmen, styling themselves “Crusaders for the Faith,” entered the church and began loudly denouncing the bishop. They alleged that he wished to replace their aging pastor. They denounced him as a Marxist and worse, and urged the faithful to leave the church. Unable to continue the Mass, the bishop and accompanying priests retired to the adjoining rectory that was pelted with stones. Eventually they were escorted from the church and allowed to leave. In the provincial capital of La Rioja, the two newspapers presented diametrically opposed accounts of the incident. One praised the bishop. The other appeared with the headline: “Bishop of La Rioja Accused: ‘He is a Communist and a Terrorist!”

The road to Anilacco: had the province of La Rioja been a world unto itself the community of Anilacco might have peacefully resolved its differences.

At the time of the Anilacco incident, Jorge Bergoglio, the future Pope Francis, was a young Jesuit priest serving as a master of novices in Buenos Aires. He had come with five other priests to make a spiritual retreat in La Rioja directed by the Bishop. Despite the problems at Anilacco, Bishop Angelelli appeared the following day at the retreat center. The encounter with the embattled bishop lasted several days and left a profound impression on the young priest. “I found a church that was being persecuted,” he later recalled, “the people together with their pastor. …I recall the affection with which he caressed the elderly, with which he sought out the poor and the sick on whose behalf he cried out for justice. Bishop Angelelli was in love with his people… He was a man who lived on the periphery, who went out seeking, who went out to meet, who was deeply a man of encounter.”

The Anilacco incident was only the beginning of a period in which La Rioja province became increasingly caught in the maelstrom sweeping the nation. Between 1975 and 1978, anti-government guerrillas were said to have caused at least 6,000 casualties among the military, police forces, and civilian population. In retaliation more than twice that number of Argentineans were detained and executed by government or paramilitary security forces. In 1977, three parish priests and a Catholic lay leader were murdered in the La Rioja diocese. Angelelli was one of the few members of the hierarchy still bold enough to speak out publicly against the government. When the bishop’s family urged him to be cautious, he replied: “You can not hide the Gospel under the bed.”

On August 4, 1973, Angelelli’s pickup truck was found overturned down an embankment along a remote highway, his body spread-eagled in the middle of the road. Police investigations were haphazard but it was widely assumed that he had been murdered.

Little was said publicly about the cause of death until Jorge Bergoglio, now Cardinal Archbishop of Buenos Aires, spoke at a Mass marking the 40th anniversary of his death. In his homily he referred to Angelelli for the first time as a martyr. “Bishop Angelelli was in love with his people,” Bergoglio declared, “and accompanied them to the peripheries both geographically and existentially… Bishop Angelelli walked beside his people to the very end…he was a witness to the faith through the shedding of his blood.”

Pope Francis’ simple life style, outreach to those in need, and his message of hope mirrors the life and words of the fallen bishop. From the moment the Holy Father has taken office, he has spoken of the need for clergy and laity to embrace a broader, deeper vision of their faith. “I prefer a Church,” the Pope wrote in his recent Apostolic Letter The Joy of the Gospel, “which is bruised, hurting, and dirty because it has been out in the streets… The Gospel tell us constantly to run the risk of face to face encounter with others…I think of the homeless, the addicted, refugees, indigenous peoples, the elderly who are increasingly isolated and abandoned, and many others…We are called to find Christ in them, to lend our voice to their causes, to speak for them and embrace the mysterious wisdom which God wishes to share with us through them. Jesus want us to touch human misery, to touch the suffering flesh of others.”

Larry Mullaly

The Christmas Sun

Christ be our light! Shine in our hearts.

Shine through the darkness.

Christ be our light! Shine in your Church

Gathered today.

Bernadette Farrell

Shepherd of the Valley Parish Church is punctuated with high overhead windows, and during the course of Sunday Mass, a stream of sunlight light makes subtle passes across the sanctuary, washing the walls, the ambo, and the altar in successive moments. This gentle interplay of light and shadow in a very quiet way evokes the mystery of Christmas.

Moderns find it hard to understand the dread so often associated with the final days of the year. But in earlier times the onset of winter promised little good. “The times are nightfall,’ the Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins writes. “Look, their light grows less; The times are winter, watch, a world undone…” For most people throughout history, the onset of winter was a downward spiral of nature in which humankind appeared to be the loser.

During the first weeks of December the days become progressively shorter, decreasing daylight by several minutes every twenty-four hours. At noon on the day of the winter solstice the sun is lower in the sky than any other time of the year. But at that very moment, something changes. In succeeding days the sun wondrously restores itself. Slowly at first and then more and more apparent, the fiery orb passes higher and higher across the sky. The days become longer and the earth is less chill.

For most of the Christian era, Winter Solstice occurred on December 25th. Interestingly enough, the earliest Christians did not celebrate Christmas. Nor did they show much concern about assigning the date of Christ’s birth. The solitary high feast of the Church year in the first three centuries was the Easter Triduum. Only when the liturgical calendar was broadened in the fourth century was the winter solstice chosen as the day on which to honor Christ’s birth.

The winter solstice is seldom noticed today. The retreat and advance of the sun have little meaning in a world that blasts away darkness with the wattage of our homes, streets, and parking lots. Through most of human history, however, work in town, home, and field began at sunrise and the precious hours –constantly changing in length — were jealously guarded. In a world in which daily life depended on natural illumination, even slight changes of sunlight and darkness were evident.

Our Christian ancestors therefore found it natural to invest symbolic meaning in the moment in which light so visibly triumphs over darkness. This perspective is still reflected in the prayers of the Feast of the Nativity. The sacred liturgies of that day tell of “the new sun now shining.” and describes how “the darkness that covered the earth has given way to the bright dawn of your Word made flesh.” The Church prays that all followers of Christ may be made “a people of this light.” The Christmas Day the Gospel of St. John evokes Christ as “the light that shines in the darkness…the light which could not be overcome …the real light which gives life to every human being…”

For over twelve hundred years, the celebration of the winter solstice and Christmas coincided. This changed in the 16th century when as a revision of the calendar caused the winter solstice to be moved forward three days while the date of Christmas was left unchanged.

Christmas has yet to come. But as the light and shadows play across the sanctuary in the next few weeks, the sun will be riding ever closer to the horizon until with the Christmas solstice it once again arises, a fitting symbol of the eternal presence of Christ, the light shining in the darkness that could not be overcome.

Walk at Dawn: Morning Mass with Pope Francis

At 7 am each day, St. Peter’s Square sits in a stillness broken by the noise of water blowing off the large fountains and the chatter of gulls. At this early hour the only life is at the hotel-like Casa Santa Marta just inside the gate to the left of the great basilica. Here the Pope celebrates daily Mass with a small group of worshippers, seldom numbering more than 50 persons. Writing to a priest-friend, Francis explains: ““In the Casa Santa Marta, I’m visible to people and I lead a normal life … I’m trying to stay the same and to act as I did in Buenos Aires.”

Photographs of the morning Mass at Casa Santa Marta are instructive. On most days a dozen or more priests or bishops are present dressed in albs and stoles. The Pope’s vestments are simple and unadorned. The congregation is mostly made up of different groups of Vatican employees, laymen and women, and nuns. Those in attendance include bareheaded women secretaries, a cluster of Swiss guards attend in ceremonial uniform but without helmets, and laymen in jackets but without ties.

Soon after his election, Francis’ practice of improvising daily homilies from brief written notes caused concern. In early April, Vatican News Services provided only the briefest of summaries of these talks. As late as May 31 they declined to provide a full text, explaining that it would require aural transcription reworking of the pope’s words. Widespread interest in these to these talks, however, caused them to appear in news stories and blogs. Today, the remarks given by the Holy Father at his 7 a.m. Mass are transcribed by a reporter from Vatican Radio or the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano and posted later in the same day on the web.

The homilies given in conversational style in Italian, sparkle with humor. “Wine,” Francis remarks, “makes me think of the wedding at Cana… Our Lady…imagined that the wedding feast might therefore end with the drinking of tea or juice: It would not do.”

An emphasis on personal prayer shines through these talks. When asked by a fellow Jesuit about the roots of his religious belief, Francis answered: “For me, faith began by meeting with Jesus. A personal meeting that touched my heart and gave a direction and a new meaning to my existence.” But there can also be a sharp edge to these remarks: “The key that opens the door to the faith is prayer…. When a Christian does not pray, he becomes “arrogant, is proud, is sure of himself. He is not humble. He seeks his own advancement.” The theme of encountering Christ frequently recurs. “How do we pray? Do we pray …out of habit, piously but unbothered, or do we put ourselves forward with courage before the Lord to …ask for what we’re praying for?” Francis speaks in terms ordinary people can understand. “The Lord,” he notes, “never gives or sends a grace by mail: never! He brings it Himself! What we ask for…is the envelope that grace is wrapped in. But the true grace is Him, Who comes to bring it to me.”

Francis applies the theology of personal encounter to all the sacraments. He describes those who refuse to speak with a priest under the pretence that they confess directly to God. “It’s easy,” he said. “It’s like confessing by e-mail … God is there, far away; I say things and there is no face to face encounter.” He applies a personalist approach to each of the sacraments. ““The Lord Jesus,” Pope Francis emphasizes, “accompanies us in our personal lives with the sacraments. A sacrament is not a magical rite, it is an encounter with Jesus Christ. ” In every sacrament, “we encounter the Lord. And he is by our side and accompanies us as a travelling companion”.

Francis places prayer at the intersection of faith and reason. “There is only one way we can understand the mystery of our salvation, Francis explains, “and that is: on our knees, in contemplation. Intelligence is not enough.” The Christian intellectual, he notes, must always be “looking at the horizon toward which he must go, with Christ at the center… to be searching, creative and generous.” But those who Christianity is purely conceptual are strongly criticized. “The faith of those who do not pray,” Francis warns, easily loses its essence, and becomes an “ideology, without a Jesus…in his tenderness, his love, and his meekness.”

A the end of the Casa Santa Marta Mass, worshippers scatter to their offices and slowly the din of cars, scooters, sirens, and horns begins to rise up from the nearby streets. The moment of prayerful reflection stands in sharp contrast to the hubbub of activity that the new day brings. Soon a long line of chattering visitors has begun arcing around the wide-armed colonnade of St. Peter’s Square as they wait to pass through metal detectors into the Basilica. At nearby Porta Santa Anna, Swiss guards in blue smocks ward off curious tourists, while a constant stream of delivery trucks, black limousines, and pedestrians into inner reaches of Vatican City. The apparatus of a busy city-state is in full operation, with consultations, public and private meetings, and ceremonies: it is all a remarkable contrast to the Mass at Casa Santa Marta, and Pope Francis’ morning walk with God.

Larry Mullaly

Wayfarers

Its branches bent and rustled,

as if they called to me:

Come here, come here, companion,

your haven I shall be!

On a warm, sunny Wednesday in summer of 2013, Alice and I took a long country walk through the hills outside of Cologne, Germany in the company of two of our friends, Uta and Reinhardt. Near the village of Blankenberg we sat for a while on a bench under a linden tree opposite a large field of ripening grain. For a while we looked on in silence. Then in a gentle voice as clear and sharp as etched-glass, Uta sang in German Franz Schubert’s classic folksong “Der Lindenbaum.”

The song tells of a wayfarer in a foreign country who inscribed his most secret wishes on a linden tree. Many years later, on a fierce and stormy night, he finds himself once again at this spot, and in the howling wind the tree assured him that he has nothing to fear: his deepest longings will always be safely held within its branches.

The beloved German song epitomizes a culture beset by the question of ultimate meaning. The tree, with its swaying branches, is variously understood to stand for the unfathomable elements of life, the mystery of nature, and some would say — the mystery of God.

Germany still considers religion to be an essential part of its cultural identity. In Cologne, throngs of visitors crowd into the cathedral to view the medieval and baroque artwork. Throughout the year, churches host concerts of classical organ music, and choirs routinely perform sacred music in Latin. Christianity in its traditional Catholic and Lutheran forms also plays a prominent part in politics. In contrast, it is illegal for a Muslim woman to cover her face with a veil, and there is little sympathy for evangelizing efforts of American Bible Churches.

We watched the wind make patterns in the wheat field, while overhead a hawk lazily circled. The Germans take nature seriously, and the previous weekend it seemed as if half the population was taking long walks, jogging, or riding bicycles. But the practice of religion is random at best. Nearly half the population still identifies itself as Catholic and pays an annual 9% supplement to their income taxes to maintain Church buildings, hospitals, and social services. Through its Catholic Charities, the German government distributes millions of dollars each year to civic improvement projects in Third World Countries. Yet only 13% of registered Catholics attend Mass regularly.

The question of belief, however, is never far below the surface. “Do you believe in God?” Uta asked me. I replied that I believe that God comes to us in Jesus. This was met with respectful silence.

Recent history has been hard on Christianity in Germany. The movement to the cities occasioned by the industrial revolution in the 1800s saw the falling away from the faith of large numbers of the working classes, while in intellectual circles a stream of philosophers proclaimed the death of God. The Nazi party, with a new purified world vision shorn of the vestiges of the past, raised a generation of young people to celebrate the nation at the expense of the church. As Germany rebuilt after World War II, young people attracted by secular values found institutional Christianity to be irrelevant. Meanwhile in the Communist East German Republic, atheism was favored as the religion of the state. All of this has impacted Germany today. “We attended a church wedding in East Germany recently,” our friends told us. “No one knew any of the hymns.” In Germany today many find it easier to admit to being an atheist than a practicing Christian.

A bird chirped on a branch overhead and such concerns seemed a thousand miles away until Uta asked me: “But do you believe in an afterlife?” There was a certain poignancy to the question. The family has recently lost a beloved relative. In America such a question would be answered by affirmations about the deceased “being in a better place,” and “looking down on us from heaven.” But in Germany such expressions do not come easily. “I believe that after death we live with God,” I answered. Once again the conversation pauses. But they were not reassured. “It is so sad,” Reinhart said, “never to be able to talk with her again.”

Faith in post-Christian Germany is a tenuous thing. During the preceding days we had visited many churches, most of which had been severely damaged during World War II and painstakingly restored. Each was immaculately clean. But a look at Mass listings reveled that the shortage of priests and worshipers has cause parishes to be clustered. A single priest serves as many as five churches. Each morning, noon, and evening, the church bells rang as they had for centuries, but the doors of many churches are locked throughout the week. We attended a Saturday evening Mass at a neighborhood parish in heavily inhabited Dusseldorf. Less then thirty worshippers were present, most of them in their 80’s. When I ask why there seems such indifference to organized religion, no clear reasons are given. It is simply the way things are.

“It would be wrong,” Reinhardt explained, “to think that most Germans are atheists. They are skeptical about belief. Only a minority would actually argue that God does not exist.” If the practice of faith is uneven, the search for meaning is unrelenting. Leading secular newspapers and magazines frequently discuss religious issues. Twenty or thirty years ago, Reinhardt explains, it was widely accepted that a person could live an ethical existence without faith in God. Now one frequently hears that a person cannot be fully human without a religious foundation.

St. Martin’s Church, Cologne: Germany

painstakingly rebuilt countless churches

destroyed by bombing in WW II, but church attendance is low.

As a people, Germans are deeply desirous of getting things right. They are concerned about protecting the environment, and agricultural districts abound with wind towers, and fields of solar collectors. They pursue perfection. Trains, busses, streetcars run with clockwork precision, and littering is unthinkable. Germans engage in social engineering to a degree unimaginable in America. Home schooling is forbidden on the grounds that it would retard a child’s development. Citizens are forbidden to run power equipment in suburban neighborhoods in the early afternoon so as not to interfere with naptime. But in terms of the deeper mysteries of being they are quick to acknowledge that they do not have the answers. All of this could change. Within societies as within individuals, movements of profound renewal are always possible. For now, however, the vast majority of Germans are seekers not finders.

Americans by contrast take religion for granted. But faith is never quite so simple. Deep down, each of us shares a part of the German soul, and in our darker moments, all of us are wayward travelers. Like the good and kind people of Germany, we too must hope against hope for that eternal refuge in a God epitomized by the strong, caring arms of the linden tree.

Larry Mullaly